- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 0

- 0

- ,

- 0

- 0

- 0

People from HIV endemic countries are over-represented in the Canadian HIV epidemic. Those particularly affected include persons under the age of 40 years and females. Most of those who are HIV positive as a result of heterosexual sex self-identified as Black. The impact on youth, females and Black populations indicates that certain populations are disproportionately affected by HIV and points to the complexity of the epidemic in Canada. In addition, a significant proportion of youth, females and Black populations are unaware of their HIV infection, illustrating the need for increase screening and treatment for specific populations.

Though Canada has more robust HIV data than other countries, more data is necessary to understand factors relating to HIV transmission among specific populations such as migrants, people of African heritage, sex workers, and men who have sex with men who are of African heritage, among others.

-MIGRANT POPULATIONS

MIGRANT POPULATIONS

AND HIV

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- .

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- M

- i

- l

- l

- i

- o

- n

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 0

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 0

- U

- n

- k

- n

- o

- w

- n

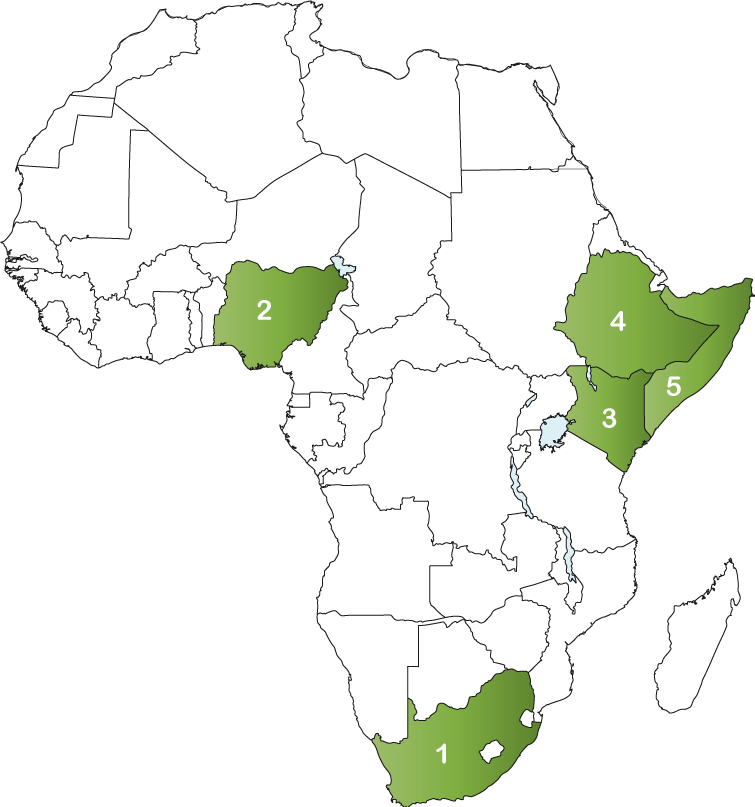

TOP 5 AFRICAN COUNTRIES

OF ORIGIN FOR MIGRANTS IN CANADA

- 1. South Africa: 47,182

- 2. Nigeria: 33,432

- 3. Kenya: 27,929

- 4. Ethiopia: 27,608

- 5. Somalia: 24,747

-TOTAL POPULATION

PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- ,

- 0

- 0

- 0

NEW INFECTIONS

- 0

- 1

- 2

- ,

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 0

HIV TREATMENT CASCADE

KEY AND AFFECTED POPULATIONS

15% of people living with

54% of new infections

Black men who have sex with men are less likely to have high incomes than their white counterparts. Pooled estimates from across the African diaspora show that black men who have sex with men are 15 times more likely to be HIV positive compared with general populations and 8·5 times more likely to be infected compared with black populations. Also, experiences of discrimination, issues with confidentiality within the context of HIV testing and treatment; poor access to antiretroviral drugs; and limited appropriate HIV prevention resources represent challenges faced by black MSM from African diasporic populations in Canada.

The prevalence of HIV among sex workers in Canada is difficult to determine. Researchers at the Ontario HIV Treatment Network have estimated that HIV prevalence ranges from 1% to 60%, among sex workers in Canada depending on their situation. Risk factors that increase the chance of contracting HIV include high-risk sexual activities with high-risk partners, lack of condom use, sharing of drug use paraphernalia, and unstable living conditions. Given the lack of data it is difficult to develop evidence informed policies and programs to serve this population.

10% of new infections

Though HIV incidence among injection drug users has been declining in recent years, a high proportion of HIV infections among women are likely due to injection drug use. In 2014, 21% of the estimated new HIV infections in women were attributable to injection drug use.

13, 960 people living with HIV in Canada in 2014 may have acquired their infection through injection drug use. It is estimated that 2,400 HIV cases were attributed to the combined category of injection drug use or sex between men since both behaviours were reported at testing.

HEALTH

The health of migrants is shaped by when they migrate, their health status in their country of origin and why they migrate. In addition, environmental, economic, genetic and socio-cultural factors play a large part in shaping health. Once in their destination country, migrants’ health is affected by their new place of residence, employment, education and poverty, the accessibility and responsiveness of health practitioners and the responsiveness of the Canadian health care system to immigrants’ health needs.

Canada has low HIV prevalence with a concentrated epidemic among key population. Immigrants and refugees represent an increasing proportion of people with HIV in Canada. This points to the need for equitable and targeted health services, education, treatment and support for immigrants and refugees living with HIV. Migrants in Canada face barriers to accessing HIV related information, treatment, and culturally appropriate support. These barriers place a significant burden on the health of migrants in Canada.

The migration journey to Canada is complex, confusing and intimidating for newcomers. Migrants with HIV may be particularly fearful because HIV testing is a mandatory part of the immigration process. Citizenship and Immigration Canada requires that all migrants 15 years of age and older undergo a medical exam. HIV testing became a mandatory part of the immigration process in 2002 (migrants who are 15 and younger and have an HIV positive parent will also be required to undergo a HIV test).

Migrants are considered inadmissible to Canada if they are a danger to the public health or safety, such as those with criminal records or those with contagious diseases such as tuberculosis. HIV is not considered a danger to public health or safety and therefore does not render a migrant inadmissible to Canada. However, like in Australia, migrants are deemed medically inadmissible if they are expected to place an excessive demand on health and/or social services compared to the average Canadian. Migrants with HIV may be considered to place an excessive demand on the health care system. Projected healthcare costs for each migrant are projected over a 10-year period. Since treatment is costly migrants with HIV may be deemed inadmissible. There are some exemptions from medical inadmissibility such as eligible refugee claimants in need of protection; sponsored immigrant applicants who are the spouse, common-law or conjugal partner of a Canadian resident; or dependent children (under 22 years of age and single) of a Canadian resident.

People who come from HIV endemic countries (most HIV endemic countries are in Sub-Saharan Africa) and live in Canada are disproportionately affected by social, economic, and behavioural factors that increase their vulnerability to HIV infection and also act as barriers to prevention, screening, and treatment programs. Factors that have lead to social and economic exclusion include racism, homelessness, transience, poverty, underemployment, and settlement and status concerns. Barriers to healthcare access for HIV infected individuals include fear and stigma, denial (as a coping mechanism), social isolation, lack of social support, fear of deportation, and cultural attitudes and sensitivities about HIV transmission.

In Canada access to medical care depends on one’s status. Refugees receive medical care through the Interim Federal Health Program which covers emergency and essential health services, including birth control, prenatal and obstetrical care, medications and emergency dental services. It also covers the cost of the immigration medical examination. Refugees whose claim is successful are eligible to apply for a publicly-funded provincial health insurance plan. The provincial health insurance plan covers the cost of all health services, including medical tests, but not the cost of all drugs. In some provinces, there may be a three-month waiting period before new applicants can get coverage.

The Interim Federal Health Program or the provincial health insurance plan do not provide coverage for medical care to people applying as immigrants, visitors, students, workers or those on a visa. Immigrants, visitors, students and workers are responsible to pay for health services and drugs through private insurance or out of pocket.

In some provinces, government-funded community health centres or health service organizations will provide free medical services to people without healthcare coverage. However, these agencies often have very limited resources and very specific criteria as to who can use these services.

Access to HIV treatment depends on one’s status in Canada. Refugees who are covered under the Interim Federal Health program are covered for HIV treatment. Immigrants students, workers and visitors are not eligible for coverage for HIV treatment and must pay for medications out of pocket. Immigration status can also interrupt one’s access to HIV treatment due to the immigration or refugee application process.

POLICY

New HIV infections in Canada continue to occur mostly in key populations, pointing to the need for more targeted policies and programs to reduce transmission and provide treatment among key population. Migrants with HIV face complex issues including traumatic and challenging migration journeys, the complex and confusing Canadian immigration system and a fragmented and uncoordinated healthcare system. Successful policy interventions to reduce inequities faced by Sub-Saharan African, Caribbean and Black migrants should be developed by engaging the community to revise and develop policies that will increase access to healthcare services and HIV treatment. Individuals from African, Caribbean and Black Communities living with HIV can often be confronted with compounded challenges when living with HIV, including stigma, racism, sexism, homophobia, heterosexism, biphobia and transphobia.

There is considerable cultural, community and religious diversity among Sub-Saharan African, Caribbean and Black migrants however, they are often grouped together for research and program delivery purposes. This limits the depth of understanding of the issues that affect specific groups and limits the success of policies designed to address the healthcare needs of those in Canada.

The misperception that HIV transmission is the result of personal choices is misleading and could be detrimental to health service provision and the policy development process. People of African heritage living in Canada are more vulnerable to HIV because of structural and systemic inequities that result in economic and social exclusion.

HIV transmission does not occur in a silo and can often be the result of social and economic environments. People of African heritage in Canada experience structural and systemic inequities that increase vulnerability to HIV transmission and as such policies and programs that prevent both transmission and poor health must be developed. Investments in equitable access to HIV treatment, access to fair and stable employment and access to housing must be made.

Though Canada provides publicly-funded healthcare, access to healthcare services is not extended to everyone. Providing access to healthcare regardless of status or what part of the refugee and immigration process someone may find themselves in may help to reduce HIV transmission and result in better health status.

THE RESPONSE

Though Canada has more robust HIV data than other countries, there is a need for improved national HIV surveillance data to better capture data on key populations. This will provide a better evidence base from which to guide prevention activities, education campaigns and policies to serve key populations. There is a lack of data on HIV exposure category and ethnicity. This would provide more nuanced data and help to clarify the various factors that lead to HIV transmission among the diverse groups that make up the HIV endemic grouping. More complete surveillance and research information would enable policy makers, public health officials, and community members to jointly develop, implement, and sustain culturally relevant prevention, education, and support services across Canada.

Founded in 2002, the Global Fund is a partnership between governments, civil society, the private sector and people affected by AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. The Global Fund raises and invests nearly US$4 billion a year to support programs run by local experts in countries and communities most in need.

Each implementing country establishes a national committee, or Country Coordinating Mechanism, to submit requests for funding on behalf of the entire country, and to oversee implementation once the request has become a signed grant. Country Coordinating Mechanisms include representatives of every sector involved in the response to the diseases.

Canada continues to contribute to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. A $650 million commitment (2014-2016) was announced in December 2013, bringing Canada’s total commitment to the Global Fund to over $2.1 billion since its inception in 2002.

South African migrants represent the highest migrant group in Canada. Please click here for Canada’s Country Coordinating Mechanism.

-SOURCES

- http://olip-plio.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Gushulak-et-al-Migration-and-health-in-Canada.pdf

- http://www.catie.ca/en/practical-guides/managing-your-health/17

- http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/CAN_narrative_report_2016.pdf (CHABAC, 2015).

- http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/epi/2010/chap13-eng.php#footnotea

- http://www.icad-cisd.com/pdf/HIV-AIDS_AfricanDiaspora_EN.pdf

- http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/canada-population/

- http://www.iom.int/world-migration

- http://www.accho.ca/en/HIV-Information/Statistics

- https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-proportion-undiagnosed-canada-2014.html#a2

- http://www.catie.ca/en/fact-sheets/epidemiology/epidemiology-hiv-canada

- http://www.catie.ca/en/catienews/2016-12-06/canada-s-progress-towards-global-hiv-testing-care-and-treatment-goals

- Millet G, Peterson J, Flores S et al. (2012a). Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 380: 341–48.

- Millet G, Jeffries W, Peterson J et al. (2012b). HIV in men who have sex with men 5. Common roots: a contextual review of HIV epidemics in black men who have sex with men across the African diaspora. Lancet 2012; 380: 411–23.

- http://www.cpha.ca/uploads/policy/sex-work_e.pdf

- http://www.catie.ca/fact-sheets/epidemiology/injection-drug-use-and-hiv-canada

- https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-measuring-canada-progress-90-90-90-hiv-targets.html